Category Archives: Life Skills

Western, Ethnic, Jewish Art – What’s Your Gift?

For the Jewish people at the foothills of Sinai, the world of the spiritual was as concrete as that of the physical.

_______________________________________

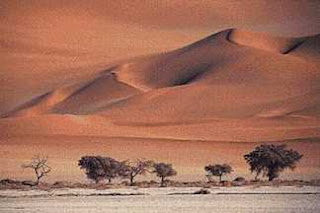

In the art of different cultures, one or other of these modalities tends to dominate. Ethnic art is largely tactile and utilitarian, albeit symbolic and conceptual. It is art that requires a close proximity and interaction between object and observer. The principal modality of Western art is visual, necessitating a certain distance between the work and its viewer. And the art of Arabian countries, according to Alexenberg, functions primarily in an auditory modality. “Its symbol, the crescent, echoes the domes of its architecture, which like the repetitive fluid patterns, envelop one like sound.” The concept of hearing is actually embodied in the name of the father of the Arabian people, “Yishmael”, which means, “God hears.” Though the art of each of these cultures necessarily employs all modalities, in each case there is one that emerges to the fore.

That the senses of sight and hearing are understood to be intimately connected with the faculty of comprehension is evidenced explicitly in other places in Jewish writings. For example, asked at Mount Sinai if they would accept and follow the laws contained in the Bible, the Jewish people responded, “We will do and we will hear, “ which our Rabbis interpret to mean, “We will do and then we will come to understand.” Seeing too is not always understood as limited to surface perception. It is associated with insight. “Some people,” says Alexenberg, “see the external and hear the internal. In Judaism, the opposite is true. Panim, “face” and P’nim, “internal” are the same word.” This dynamic interplay between seeing, hearing and understanding of both surface and interior, is reflected in the way the command “understand” is translated in the Talmud and the Zohar. In the Babylonian Talmud (the revealed, legal aspect of oral Jewish tradition) we find the word tashma, “come and hear,” whilst in the Zohar (the concealed, mystical dimension of the Torah, the name itself connoting “glow”) we read tachazeh, “come and see.”

The Temple he built was the epitome of beauty because King Solomon had the ability to penetrate the interior in a way that echoed the the Jewish people’s perception of the spiritual at Mount Sinai.

_______________________________________

The union of the aural and visual, a perception that penetrates beyond the surface to the interior, is as essential to Jewish art as it is in its religious literature. This vital interplay between surface and interior existed in the first Temple, one of the most glorious manifestations of multi-sensory Jewish artistic expression. We find it alluded to in the writings of Rashi, a foremost commentator on the Bible of the twelfth century. On the clause, “and God shall dwell in the tents of Shem,” Rashi states that God’s enlarging of Yaphet refers to His enabling Cyrus, of the descendants of Yaphet, to build the Second Temple. Rashi continues, “Nonetheless, there did not dwell in it the Divine Presence. And where did it dwell? In the First Temple, which King Solomon built.”[2] The First Temple is perceived as being on a higher level than the Second precisely because it housed the divine Presence. Yaphet, the visual, no matter how masterful, was not sufficient for creating a complete beauty. King Solomon, one of the most righteous of Jewish leaders, was able to actualize the ideal of “Chen.” The Temple he built was the epitome of beauty, because King Solomon had the ability to penetrate the interior in a way which echoed the Jewish people’s perception of the spiritual at Mount Sinai.

The interplay required in Jewish art is not only one between the different senses, but extends to the physical and spiritual dimensions of our lives. This is not surprising given that dynamism is a fundamental aspect of Jewish consciousness in general. As Alexenberg notes, “The first time we read of a Jew, Abraham, in the Bible, is in the portion entitled Lech Lecha. Lalechet meanst to walk or go. The word for Jewish law too, halacha, coming from the same root, reflects this dynamism.” Commenting on an article sent to him by the Lubavitcher Rebbe, he points out that the word for spirit, ruach (raysh-vav-chet) and the word for matter, chomer (chet-mem-reysh) are intimately related when inverted since the letters “vav” and “mem” are interchangeable in the Hebrew alphabet. “Unlike certain traditions where you have to renounce physicality in order to attain spirituality, in Judaism they are essentially one. All that changes is one’s angle of vision, the way we perceive. Jewish art is about the spiritual nature of one’s encounter with the physical world.” Since this encounter is constantly changing, so too Jewish art must be ever dynamic and responsive to its surroundings.

_____________________________________________________

Jewish are is a multi-media, all involvement event.

_______________________________________

Such dynamism entails an open-endedness and necessity for active involvement on behalf of both artist and viewer which is paralleled in the “happenings” of the art world of some decades back. Happenings attempted to break the passive observance of traditional western art by incorporating the audience into a process or event which was in itself, or out of which rose, a final “artistic product.” Alexenberg contrasts Jewish art with, for example, the more passive process of traditional Western theatre. “Jewish art is a multi-media, all-involvement event.” He perceives the Pesach Seder and the Sukkah as examples of Jewish “happenings.” “We follow a text, the Haggada, at every Seder. There is a narrative flow, but it is not linear in the sense of a classic text. We have the four cups of wine, the children running after the Afikomen, the Charoset, the bitter herbs which bring tears to our eyes. The audience and the performers are the same people. It’s a multi-sensory, multi-media happening. A Sukkah is the same thing. We have a chance to get out of the house, the world, civilization…and observe. Yet we are inside and outside at the same time. I remember discussing with Alan Kaplan, innovator of the first happening, as to how he developed the concept. It grew organically…I mentioned to him the parallels between happenings and the Pesach Seder and he saw the correspondences. Having himself sat around a Seder table, he subconsciously had the parameters of a happening there all the time.”

[2] Rashi on Genesis 9:27